In the desert heat of Aleppo, Thomas Darley was checking out a horse. He was in Syria working as the British Consul, but he knew a beautiful horse when he saw one, and this one was particularly striking. He was a young colt, 1 or 2 years old, a bay Arabian, which was common to the area, but taller than others of his age. This horse held itself with such elegance that Darley thought he would be great to send back to his family’s estate in England.

He proposed purchasing the horse for 300 gold sovereigns, which the horse’s owner agreed to. But, the seller had remorse almost immediately and changed his mind, canceling the deal. Darley still wanted the horse though, so he did what every reasonable person does, he offered more money- no wait, he arranged for British sailors to steal him, and they smuggled him back to England.

So the story goes, anyway.

The horse is question would become known in history as the Darley Arabian. It’s not totally clear if Thomas Darley paid for the horse, or how he paid (another story says he paid with rifles), but Darley saw that horse in Syria, and knew he was special. His instincts were right (the eye for horses instinct, not the stealing instinct), as The Darley Arabian became one of the three foundation stallions of the thoroughbred breed. The Darley Arabian bloodline is said to be present in about 95% of today’s thoroughbreds.

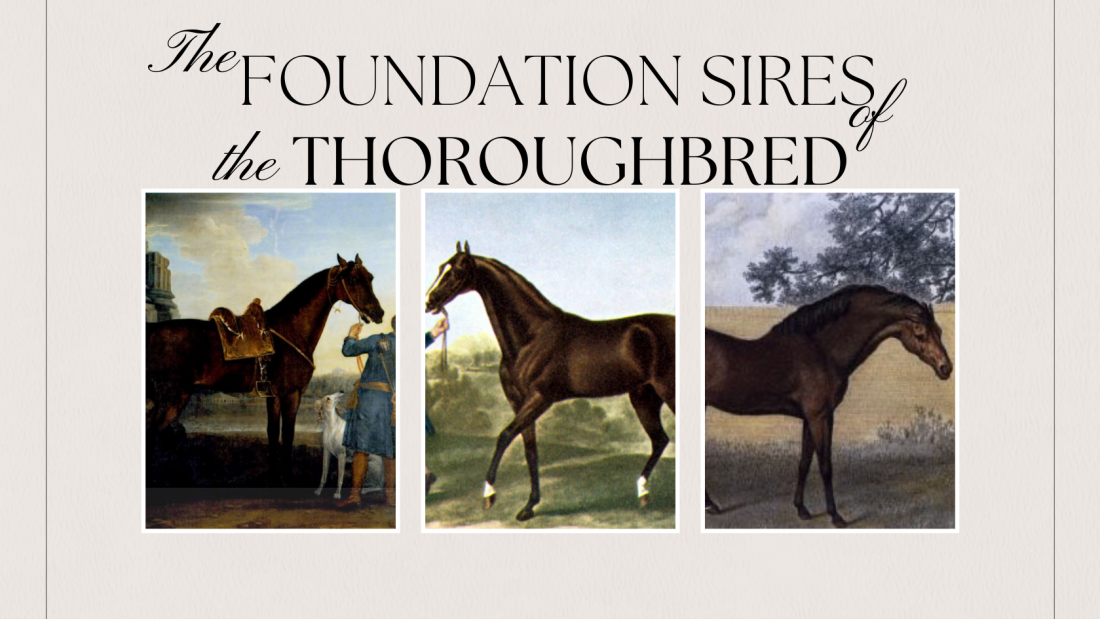

Thoroughbreds, a British breed, have their surprising origins in the Arabian Peninsula. In the late 17th century and early 18th century, when three stallions were brought to England, the Darley Arabian, the Byerley Turk, and the Godolphin Arabian Who were these horses, and how did the thoroughbred come out of them?

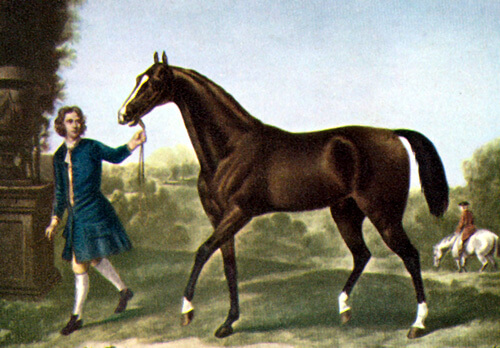

The Darley Arabian (1700 – 1730)

Thomas Darley wasn’t sure if his new horse would be liked in England. Despite his obvious good looks, he was very different from the heavier style of horses already in England. At one point, he wrote to his brother, trying to explain the value of the horse, telling him that the horse was a pure Arabian strain, descended from the “Muniqui” lines. This line of Arabians was developed thousands of years ago by the Bedouin tribes. They have a light build, are very fast, but don’t have as much endurance as other Arabians.

Either his persuading worked, or he just tried as an experiment, but the Darley Arabian was quickly moved to the breeding shed. The cross of the light, fast Arabian, and the heavy English mares was immediately a hit. Although he himself never raced, his offspring were quickly on the racetrack. He had a long career as a sire, from his arrival in England in 1704, all the way to his death at the ripe old age of 30, in 1730. In 1722, he was the leading sire in all of Great Britain and Ireland.

The little stud sired an incredible amount of well know horses. Flying Childers was undefeated on the racetrack and considered the first truly great thoroughbred racehorse. Bulle Rock was the first thoroughbred to be exported to America in 1730. And then there was Bartlett’s Childers, who was unraced himself, but was the start of the line that led to Eclipse, an undefeated racehorse, and considered the greatest racehorse of all time. He was also the start of the lines that lead to the modern descendants, Northern Dancer, Mr. Prospector, and Sunday Silence.

The Byerley Turk (1680 – 1703)

After 78 days of fighting, the battle was over, and the Ottoman forces that had been occupying Buda, modern day Budapest, for almost 150 years had been defeated. The Holy League, an army of united European countries, had been working for years to push back the powerful and ever expanding Ottoman Empire. Filled with rage at their enemy, the united armies continued their attack, targeting civilians and plundering whatever valuables they could find.

Colonel Robert Byerley was part of the English forces. As the city went quiet, he saw a lone stallion, a leftover from the battle. His rider was long gone, likely killed in battle, and the stallion was loose. He liked the look of the horse, so he, like many others taking the spoils of war, captured it. When he went back to England, he took it with him.

The Byerley Turk, as he became known, was a war horse. Although accounts of how exactly Byerley found him vary, he was described as an Arabian of unknown breeding. He was noted for his elegance, courage and speed. Byerley continued to use him in battle for the next ten years, and he proved to be a faithful companion. In one instance, Byerley was nearly captured, but managed to escape, “owing his safety to the superior speed of his horse.”

When Byerley retired from military service in 1693, the Byerley Turk also retired, but to a second career. He became a stallion at stud until his death in 1704.

The Byerley Turk line is not nearly as prominent at the Darley Arabian line. His modern thoroughbred line is from Harod (who also has the Darley Arabian), who lived from 1758-1780. But outside of racing thoroughbreds, the well known show jumper, Gem Twist, is a descendent. The Byerley Turk has also been prominent in other horse breeds, including Morgans, Quarter horses, Standardbreds and Saddlebreds.

He also had an influence on European warmblood breeding. Ramzes, who was a descendent of Harod, had a huge impact on the German warmblood breeds. Most notable is the Westphalian stallion Rubinstein I.

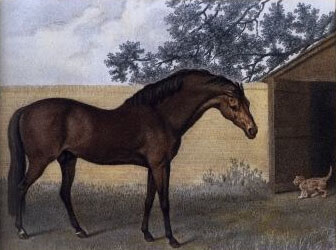

The Godolphin Arabian (1724 – 1753)

When King Louis XV of France came out to inspect his new horses, a gift from the Bey of Tunis, he was not impressed. A bit underwhelmed really, he was expecting so much more from the famed stud. He accepted the gift, but quickly moved on to something more interesting. The horses could pull the carts or something, he didn’t care.

The horses did unremarkable work, until one of them was purchased and imported to England by Edward Coke. The horse was a small bay stallion with a very high crest, and not considered particularly attractive to most.

Coke didn’t mean for the horse to be a sire. He was originally used as a teaser stallion, but one of the mares, Roxana, rejected the intended stallion, so they allowed the horse to bred to Roxana instead. The resulting foal, Lath, turned out to be an amazing racehorse. Coke didn’t last a whole lot longer after that though, and the horses were willed to a friend of his, who in turn sold to the horses to his namesake owner, the 2nd Earl of Godolphin.

Naturally the first thing Godolphin did with his new stallion and mare was repeat the breeding, two more times. The three foals, all colts, were all identical, the spitting image of their sire, of small size, golden bay coats, and, most importantly, speed. The Godolphin stallion was a prized stud for the Godolphin, continuing to sire more, but his three went on to sire many foals themselves, spreading the Godolphin line far.

Several well know thoroughbreds today can trace their lineage back to the Godolphin Arabian including Seabiscuit, Man O’War and War Admiral

the General Stud Book

As time went on, the breeding continued to evolve. People continued to breed for the fastest, but when the Jockey Club was officially created in the mid 1750’s, they begin enacting rules for racing (much less fun than the previous free for all). The racing format also changed. Early races were lengthy, up to 4 miles in length, and often done in multiple heats. The Arabian, the master of endurance rides, was great for this. But, the format changing, and races grew shorter, eventually shrinking down to a mile or a 1.75 mile. The horses that could excel in that were bigger, with longer legs, and lengthier strides.

People begin to wonder, has the thoroughbred reached the maximum amount of Arabian?

In 1885, this was tested. a mid-grade level thoroughbred, Iambic, was put against a winning Arabian, Asil. It was a race over 3 miles, and the thoroughbred carried extra weight to handicap him. But even with this, the thoroughbred won by a full 20 strides. This answered the question, that yes, the thoroughbred had reached the maximum level of Arabian, metaphorically closing the book on future crosses.

The General Stud book, created by James Weatherby in 1791, was the first official record of the pedigrees of British racehorses, becoming the official thoroughbred record. This was a huge project to take on, and Weatherby traced back most of the racehorses for 100 years, showing the links back to the three Arabian stallions.

Thoroughbred record keeping also apparently became a family business, and even today, the Weatherbys continue to hold the records.

The Arabian breed contributed much to many other breeds, and had a huge impact on thoroughbreds. Even though this three stallions are the most well know, many other Arabians and barbs also contributed, and I’d say the British mares did their part as well. It was a group effort, really, of many, all working together for a singular goal – winning a race and showing up the neighbors. Just kidding, sort of.

Many great horses exist today because of these three and their fascinating stories, and we can appreciate them a bit more, knowing how much effort it took to get to this point.

Real Life Versions of Animated Disney Horses - Part 1 - An Equestrian Life

[…] Using this impressive analysis, Aladdin takes place in the 15th century, in the Ottoman Empire, which is now modern day Turkey. Arabians horses were widespread in this area at that time, with many local tribes breeding different varieties. One stallion from this area even ended up being one of the foundation stallions of the thoroughbred breed. […]