Horses are the foundation of military power, the great resources of the state but, should this falter, the state will fall.

Ma Yuan (14BC – 49AD, Han Dynasty Military General and horse expert

When Emperor Wu came to power, the Chinese had been using cavalry for the previous 200 years. Before that, chariots had been used in battle, but they had many disadvantages, all of which became apparent when fighting the horse riders of the nomadic tribes. Their riders were agile, darting around chariots and infantrymen alike, while the chariots were heavy and cumbersome, unable to react fast enough to keep up.

Even after they adapted horseback riding in battle, the Chinese knew the horses were of inferior quality, slow and weak, with very little endurance. A huge factor was likely the inadequate pasture for the horses. They did try to remedy that: The best grazing land was already occupied by civilians, but that didn’t mean much, they were forced off their land so the imperial horses would have land to graze.

But still, Emperor Wu dreamed of a better horse, one that would enable him to fulfil his military dreams.

He would get his answer in the Heavenly Horses of Ferghana.

Who Were the Ferghana Horses?

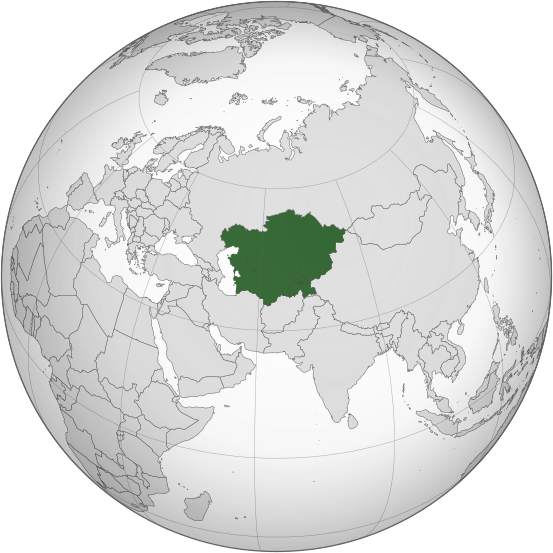

1. They Were Originally From Central Asia

Although they are most commonly associated with ancient China, they actually originated in central Asia, specifically in the Fergana valley, which is now modern day Uzbekistan.

The fertile valley was in between two rivers, and along the Silk Road Trade route. It has settlements dating back 2300 years, including one from a conquest of Alexander the Great in 329 BC. The area of the valley called Dayuan was settled by Greek colonists. The decedents of those Greeks would be the ones that bred the heavenly horse, bringing the military force of China to their doors.

2. The Han Dynasty’s Campaign to to Get the Horses

Emperor Wu was the seventh emperor of the Han Dynasty, reigning from 141 to 87 BC. During his reign, he led a great territorial expansion, and opened up many regions previously blocked to China. This included the route along the Silk Road, going right through the Ferghana Valley. With the trade route open, they were introduced to many things they hadn’t seen before – like the Ferghana horses.

Emperor Wu had previously divined by the Book of Changes (I Ching), which told him that “heavenly horses” were going to appear from the north west. He originally thought it was a different horse, but once he saw the Ferghana horses, he knew these where the horses.

Emperor Wu first set out to acquire the horses through normal means. He sent his envoys to the region to check things out, and to buy some of the horses. You know, the normal way people handle transactions. But not only did the Dayuan king refuse to sell, he also stole their money – and then for good measure, killed them on the way out.

Naturally, this made Emperor Wu pretty upset, so he set out to get the horses by another way. In 104 BC, he sent his army. The road to Dayuan was long and hard though, and they lost many of their army just traveling there. The army was defeated, but Emperor Wu wasn’t giving up that easily. Two years later, he sent an even bigger army, of 60,000 men.

This time, he managed to get somewhere. Despite losing 50% of his army just getting there, he managed to place the city under siege. The inhabitants threatened to slaughter all the horses, but eventually they reached a compromise.

Emperor Wu was given 30 of the heavenly horses, of the highest quality, so he could breed his own heavenly horses. They also gave them 3,000 horses of lower quality, so they could replenish their cavalry. They also presented him with the head of the King that had previously slaughtered Emperor Wu’s envoys.

China now had the Ferghana “Heavenly Horses”.

And, in a bonus, they also brought back a new grass seed to sow, similar to alfalfa. Chinese horses were about to get a major upgrade.

3. The Heavenly Sweat

The most distinct feature of the Ferghana horses was their ability to sweat blood. They are known in Chinese as Han Xue Ma, which literally means, “sweats blood horse.”

Even now, we could say that a horse sweating blood is definitely unusual. To people back then, it was mythical. The stuff of legends.

Today it is theorized that the bleeding was likely caused by a parasite that specifically targeted the heads and upper forelegs of the horse. The parasite burrows into the subcutaneous layer, resulting in the skin nodules bleeding often. This parasite is widespread across the Russian Steppes.

So this is a good theory, although it’s unclear why it only effected the Ferghana horses, and not all horses.

A second theory is that the blood vessels in the horse would burst after a hard gallop. Maybe there was something specific to the Ferghana horse that made for thinner blood vessels. Maybe it was a combination of thin blood vessels and the parasite.

4. A Thousand Year Legacy

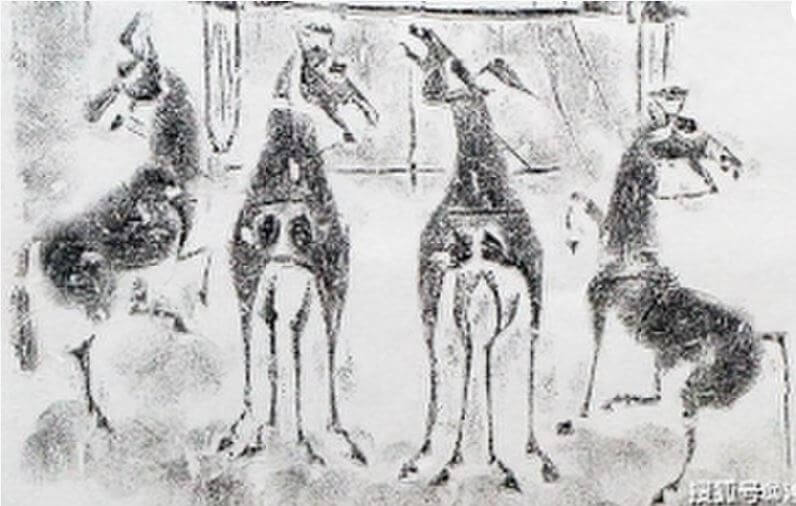

Although the Ferghana horse existed in a time before photos, they have been frequently portrayed in Chinese art.

They are stout, with short legs. Their necks were high, with thick crests and noble looking faces. They were known to be fast, with great endurance. This made them excellent cavalry mounts, as Emperor Wu continued to expand China’s territories. Emperor Wu eventually doubled the size of China, with much of the land part of China today.

The horses were considered status symbols. They were an elite breed of horse owned by the most wealthy members of Chinese society. They were immortalized in statues and paintings. Mythological stories are based on them. The Tianma was a winged, flying horse, sometimes depicted with dragon scales. It also had the habit of sweating blood.

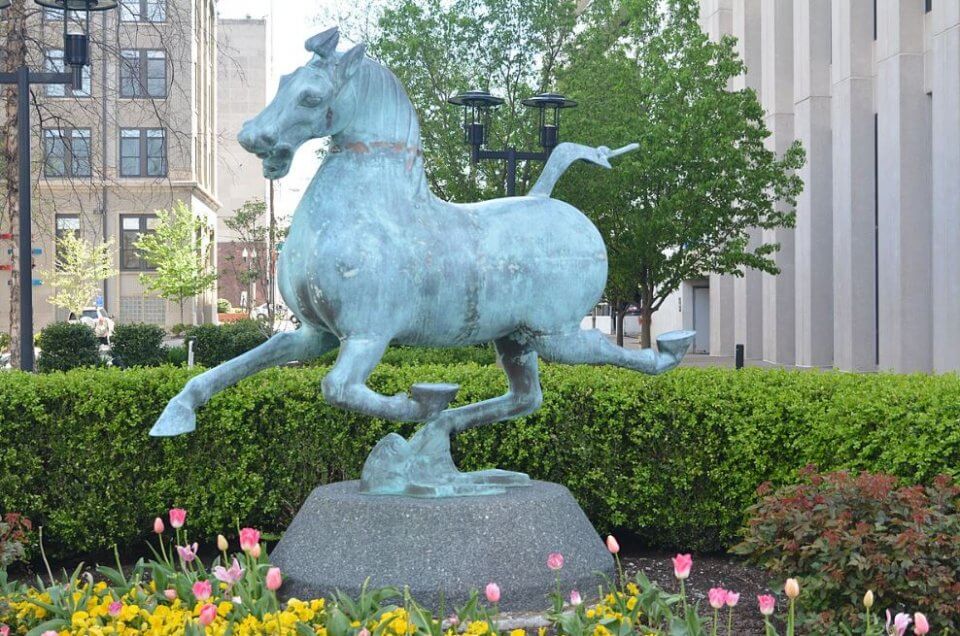

The Flying Horse of Gansu Statue is one of the most famous works of art. It was discovered in 1969 when war with the Soviet Union looked likely. Workers were digging to construct an air raid shelter, when they found a chamber underneath a monastery. It turned out to be a three chambered tomb belonging to a Han Dynasty army general.

The tomb was filled with over 200 bronze figurines of men, horses and chariots. One of them was the Flying Horse. This horse was portrayed in a huge trot, with one foot holding up the entire statue. The foot is believed to be resting on the back of a swallow.

The Ferghana horse was popular for a thousand years, but over time the needs of the people shifted. The Ferghana was fast with high endurance, but it was also small and lean. Over time, the demand for larger and stronger horses grew in China. This led to the decline in popularity of the Ferghana horse, and eventually, it led to its extinction.

5. Ferghana Horses today

Today some claim that the Akhal-teke breed to be descendants of the original heavenly horses, the Akhal-teke. This breed also originated from central Asia, but it’s difficult to prove their exact bloodlines, as keeping records on horses wasn’t a big priority. But, as they are also an ancient breed, it’s completely possible they existed at the exact same time as the Ferghana, so it would be hard for them to be formed from them.

The Akhal-teke is known for its distinctive metallic coat and athletic prowess. Just like their possible ancestors, their numbers are in decline. Current estimates is at 6,600 horses today.

The Akhal-teke might be the closest possible relative of the Ferghana, but is it possible that the Ferghana still exists? The breed was declared extinct. So why are there reports of Ferghana horses still in China?

In 2010, China Daily reported that three Ferghana horses were imported into China from central Asia by Beijing Yanlong, a horse dealer. The horses were to be put up for auction, with starting prices of 5 million Yuan, equivalent to $738,552 back then.

The prices certainly seem realistic for a super rare, “extinct“ breed. But are they actually the heavenly horses from ancient China?

This horse is being called the “blood sweats horse,” which would indicate it is the true Ferghana. (although I have yet to see photos of the blood sweating). It seems most likely that these are Akhal-teke horses that are being called Ferghana, either from a translating error or maybe they do believe it’s a close enough relation. It’s impossible to know without further information, including breed records and DNA testing.

In 2013, another Chinese horse breeder came forward to say he also has Ferghana horses. He directly references that they are from the Ferghana valley, and 3,000 of these horses remain. The prices certainly seem in line with a rare breed of horse, ranging from $325,000 and $49 million.

Are these horses somehow back from extinction? Or is this an Akhal-Teke in disguise?

Only time will tell – there isn’t a lot of information out there (at least not in English). I’m actually quite fascinated by this, so I hope more information will eventually come out. Be assured, if I ever see an update, I’ll be posting about it.

Janet

Perhaps this article will complement your article, thank you https://www.labrujulaverde.com/en/2024/04/how-chinas-han-dynasty-got-the-heavenly-horses-to-create-its-mighty-cavalry/

Anonymous

1′”