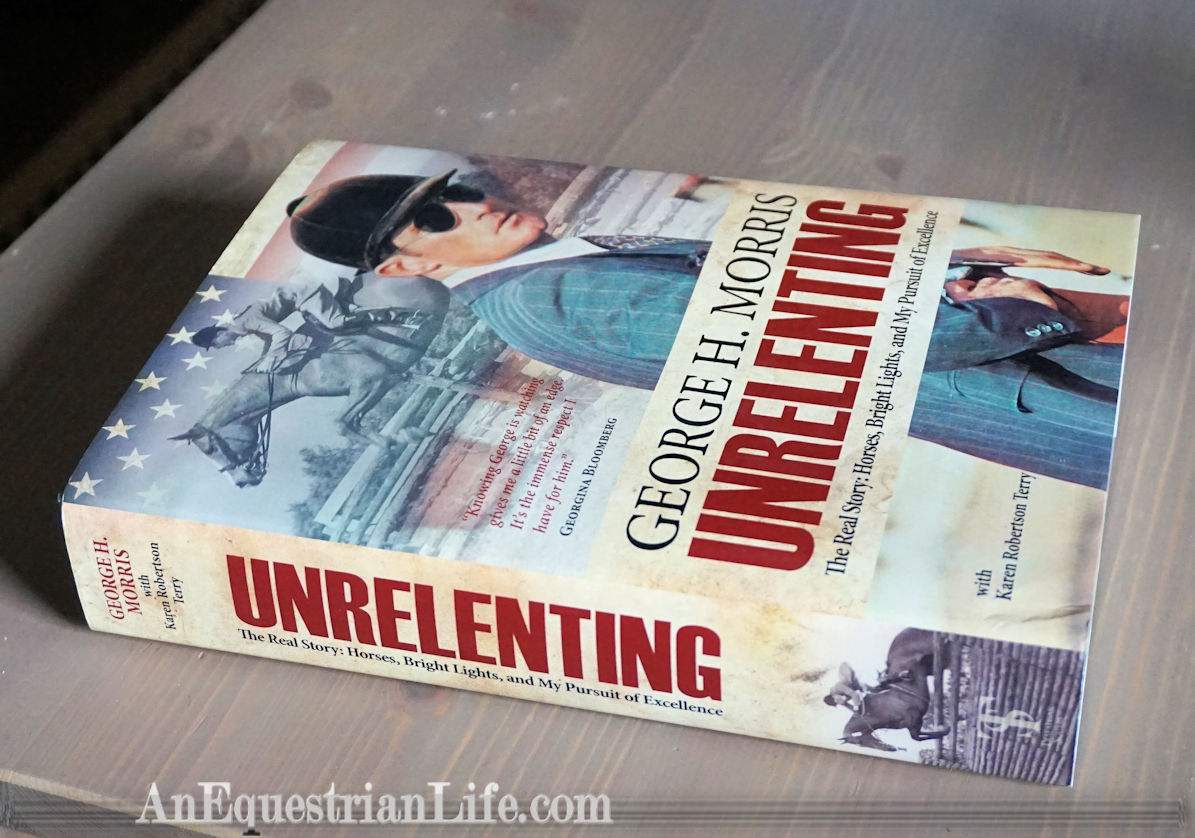

If you are at all serious about jumping, or possibly even riding a horse, you know who George Morris is. He is impacted hunter/jumper riding in such a monumental way, it’s impossible not to know who he is. One of my very first books on riding was George Morris’s Hunter Seat Equitation.

If you ever wondered how George Morris became George Morris, here’s the answer, in the form of 400+ pages.

I’m sure I will be tarred and feathered for saying this, but at first, I didn’t like this book. It was an explosion of names, and hard to read. I forced myself to keep reading it, because it’s George Morris after all, but I was having difficulty getting into it. In the end, I’m glad I did, but those early chapters were tough.

It is not a novel, and I think part of my issue with this book is that I usually read novels, and therefore expected that format. It’s written exactly like how life really is, full of experiences, not all of which are remotely related to each other. There’s no overarching story line to follow, there’s no building up of the story, and no climax. There was no point where he said his overall goal was to do “x”. Granted, when you’ve accomplished as much as what he’s done, perhaps there’s nothing to aspire to. But it felt kind of like he was just bumbling along, with everyone in his life giving him exactly what he needed or wanted, with no struggle at all.

The book is divided into sections by the decade, and each one is written like a series of anecdotes. Very short stories, a paragraph long, and then right into the next anecdote. The result is very jarring to read, and it ends up being a blur of names, places, and horses. One paragraph he’ll say he rides at a certain barn, and then next one, he just got a puppy at a show, and the next one, he’s partying in New York. There’s no distinct story line, motive, or lesson to each chapter, no climax, just, “here’s what happened. Then this happened. Then this happened.”

Still, the tidbits about lifestyle in the 50’s was really interesting to hear about. Lessons were only $3, and they took place outside the ring, learning while riding around the countryside, which of course, still existed, with lots of woods, fields and trails. Horses were a social lifestyle of time, along with hunt clubs and balls, and his family was extremely supportive of his riding career.

At one point, he was talking about deciding what to do with his life, and he sounded just as lost as some young adults these days. He eventually picked horses, although it seemed as though he mainly interested in making a career with horses because he had no skills in anything else. Although he did attend a theater school for two years, which I did not know.

“Gordon Wright used to say that my stage fright worked for me. For some riders, it works against them. It can prove to big advantage learning to use your nerves to make you sharper and more alert, rather than letting them paralyze you.”

George Morris was given many talented horses to ride, and it was interesting to hear about how he worked with their personalities, not against them. He even recounts when he used a very heavy handed with a sensitive horse, and the horse was never the same again with him. He learned a lesson that he had to adapt to the horse, and not change up the ride.

His early life sounds a lot like many young people’s lives. He describes relationships, drugs, partying, and how it related to his horses. Sometimes, it’s almost surprising that he accomplished the amount he did, since it seemed like he really liked his partying.

“…Years later, I taught a clinic at her farm in Tennessee and it was like Old MacDonald’s with farm animals everywhere; I had to chase chickens out of the ring during the clinic!”

I felt like the book got more interesting in the 70’s decade. It seemed easier to read, and I think it helped that I saw familiar names. The anecdotes were still there, but they seemed to flow into each other better. It was also fascinating to read about the changes to jumping courses, and how it created change throughout the way everything was done.

“The horse show schedule wasn’t as grueling as it is today, with more time for learning and working with horses at home. When we did show, it was extremely competitive with hardly any beginner classes. Hunters still galloped over big, outside courses with fixed natural obstacles. That training was combined with the technical advancements seen in the sixties – riders were expected to be more proficient with dressage flatwork and to relate distances and demonstrate flying lead changes on course.”

The 70’s also was the era George Morris “grew up”, so to speak, and found a home base. Perhaps with him not running a muck anymore, it centered this book a bit. At this point, I was unable to put the book down.

He taught throughout his whole life, and there’s lots of blurbs from riders he developed on their experiences with him. Some brief encounters, other lifelong friends, they all share what riding and life lessons he helped them learn. Other times, they share a funny bit of gossip.

“…George was very central to women excelling in the sport of show jumping during a time when women were still redefining their role in our country.”

-Armand Leone

Reading about his part in changing riding technique world wide is awe inspiring. I did not realize his teaching had made such serious impact on the global equestrian world. It’s incredible the amount of change one man brought about. He describes the American’s taking European show jumping by storm, and their shock at being beaten by them.

“The Europeans, who once had laughed at us, were suddenly on their heels trying to catch up!”

He has an obvious pride in his work, and in American’s efforts in global equestrian competition in past years. It made me want to sit up straighter, and ride better. Alas, I’m not at any high level, so in the end, my American pride will stay small.

I found the most intriguing parts of the books where the ones describing the personalities of the high level horses, and the riders. I was surprised that he thinks a horse that’s a chicken is actually a better jumper than a brave one, but it does make sense. A chicken jumper is going to be more careful not to touch the jumps. With that kind of personality though, the rider 100% needs to be the brave and confident leader. Professionals had to be very careful about their rides, because the horses are so sensitive or special needs. It requires finesse that can only be gained through the amount of hours they put in. Now I understand better why some horses would be called a “Professional’s” horse, vs. an amateurs.

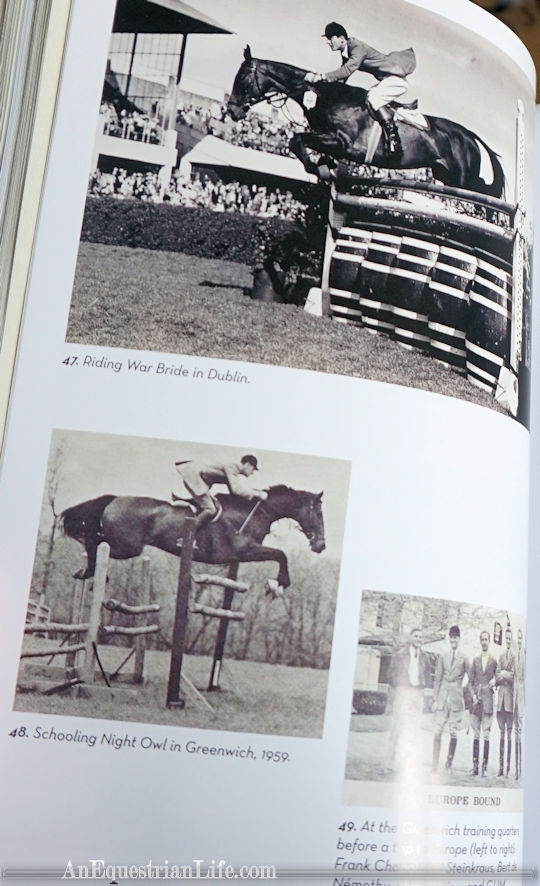

Many sections of just photos.

This isn’t a book about training techniques (except for those mentions of old timey poling…) or how to be a better rider. But I was getting one message loud and clear. Being a good rider takes a mindset. It’s about being brave, thinking quick, and pushing through fear. Talent is important, but the most important thing is putting in the hard work. Which means, ride way, way more.

Overall, I really liked this book. As I said, it was difficult to get into, but it might flow better with a second read. I do think they should have choose a different format for the overall story. Chronological does make sense, but it would make sense to further divide into shows, or clinics, or horses. Just something so it’s not a huge mismatch of everything together, and there’s really no way to tell which parts were more meaningful. Because the way it is now, there’s no sense that him buying a horse in Virginia is more or less important than him going to the Olympics, or getting a drink in New York.

I still think it’s great that GM’s life was finally written down for the rest of us. I think anyone who has any ambition to accomplish anything close to what he did will appreciate knowing how he got there. Since the book goes into so much detail about hunters, jumpers, and equitation, it could also be considered a history of how those classes have developed over the last 50 years, as he talks a lot about the changes to the courses, formats and styles. It’s like a history of GM and jumping rolled together.

It does end on a bit of a sad note. After all of this, what is there left for GM to do? Hopefully he will continuing clinicing for a long time to come, and I’ll be able to squeeze in there next time he comes around. One of the things I really liked in interviews in the book, people described him being equally willing to help out beginners and experts. Anyone who puts in the hard work, he will help.

But know he is disappointed that the American’s haven’t kept up with their domination in global show jumping. It ends as almost a call to action – American showjumpers, and American horse owners, come together to show for America, like how it used to be. I wish I could help George Morris, but my Berry is not a talented jumper, nor am I. But you have inspired me to ride. Maybe if I get my butt in gear, I can start accomplishing some cool things like you.